I have near two year experience doing oversea marketing from a leading international NAS company called Synology. My role was devising marketing strategy and implementing it in our New Zealand and Australia market. (These two markets earn Synology over 1 billion revenue annually) I was the only marketing person who looks after these two area, so I have to run user/market research, devise product and content strategies, build campaign website with development, hold offline trade shows, perform copywriting, release product PR/ writeups and strategically distribute all the marketing materials to various channel outlets (including enterprise and consumer channels).

I came across UX in a marketing campaign where I design the website from scratch and attracted millions of impressions within two months. I realized that I’m interested in how experience shapes user behaviors, as well how they make decisions. By looking into users in both qualitative and quantitative lens, I hope I can play a more product-oriented role in a firm. That’s why I decided to pivot my career.

Thanks for reading these long paragraph and would love to hear any suggestions from you!

Hello, Daphne, Sorry about the delay. I read your note with interest; since you have some experience in product marketing you might be more ready than your peers to engage design goals at a higher level.

Design goals are the marriage of user goals and business goals. The ideal product, design, or business intervention brings success to the person being served and the business doing the serving.

In my early days at a past employer some product management leaders arrived from Procter & Gamble. They brought a method of product definition that changed the way I look at design. To hear them tell it, a solid product concept depends on some insight about a customer, some insight about the competition, and a way of delivering a benefit to that customer in a way that is informed by these insights and thus distinct from your competitors. It may not have a direct competitor at all, if your insights are insightful enough.

An insight is a statement of fact about a situation or behavior that is obvious in retrospect, but hidden or overlooked to most observers. An example: if you ask married men in the US why they shave their faces, they may say something about their spouses liking them to have a smooth face. But if you examine common shaving behaviors you’d see these same men shaving on weekday mornings before work, and letting their stubble grow on the weekend, just when they’d be spending the most time with their spouse. Clearly their motivation is elsewhere; it turns out that their behavior demonstrates that they shave to demonstrate a professional appearance at work.

A benefit is the result of having or using your product, expressed in general terms. It’s especially important that the benefit be a result, rather than a product itself. It’s also important that the benefit be expressed in general terms; the benefit could perhaps be delivered by means other than your product. In the shaving example, the benefit of a comfortable, smooth shave every morning could be delivered via a razor, or a shaving powder, or perhaps carefully-targeted lasers. The method is important, but the benefit does not state it.

I mention these product marketing concepts, benefits and insights, because interrogating them can usefully inform the work of product design and help others on the team, such as engineers and QA people, understand the intent behind the product being developed.

Asking about benefits and insights can also help you detect where research may be needed to strengthen the case for a product, to improve the benefit, determine how to demonstrate the benefit, or even where the product management is lacking. It’s common for newer product managers to rush headlong into assignments where they are asked to deliver a feature without really delving into the benefit that feature is meant to deliver. During design and development the forces of budget, timeframe, and technology can distort a poorly-understood benefit and put the design and development effort at significant risk. Attention the the benefit, why the benefit is relevant, and the various means available to you of delivering the benefit, can help you craft an intervention that is at the right scale for the business and really meets a customer need.

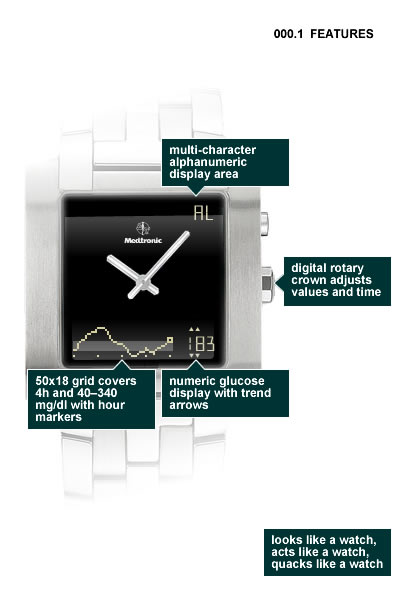

There’s one more product marketing concept that is important here: reasons to believe. A reason to believe is a fact about the product that helps the consumer understand that the product really will deliver the benefit it promises. RtBs come in many forms, such as endorsement (Kobe wears these shoes, the American Dental association recommends this toothpaste), explanation (a diagram of the product in use, a video), demonstration (see my white teeth), comparison (this router is 15% faster than the leading brand), proof (clinically proven to reduce cavities), a visible feature, a named feature, reassurance (money-back guarantee), or a testimonial (Joe here really enjoys his stump jumper).

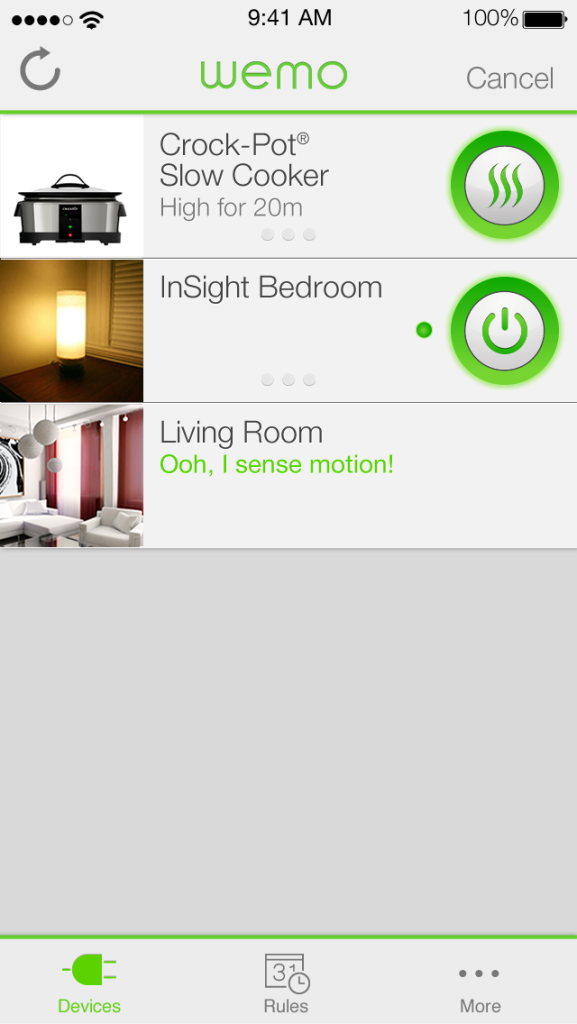

If you are working on a feature for a product, and you understand the benefit, you can more easily give your user the scent of that benefit early in the interaction and demonstrate that you have delivered the benefit later in the interaction. This is just good design practice, but by asking the right questions you can get to a potentially successful design faster.